W obliczu rosnącego napięcia na Bałtyku, 3 lutego Marynarka Wojenna RP przeprowadziła ćwiczenia „Strażnik Bałtyku-25”. Ich celem było doskonalenie procedur reagowania na potencjalne zagrożenia. Szczególny nacisk położono na wykrywanie, identyfikację i kontrolę niezidentyfikowanych jednostek operujących w pobliżu polskich wód terytorialnych i infrastruktury krytycznej.

W artykule

Głównym założeniem ćwiczeń było przechwycenie i zabezpieczenie jednostki morskiej, która nie odpowiada na wezwania i podejrzanie zbliża się do polskich instalacji wydobywczych na Bałtyku. W tym przypadku chodziło o tzw. statek floty cieni – jednostkę, której transpondery systemu AIS są wyłączone, a załoga nie reaguje na próby nawiązania kontaktu.

Tego typu sytuacje stanowią realne zagrożenie, zwłaszcza w kontekście możliwych działań dywersyjnych, takich jak podkładanie ładunków wybuchowych czy niszczenie podmorskiej infrastruktury telekomunikacyjnej i energetycznej.

W odpowiedzi na zagrożenie do akcji wkroczyły jednostki Morskiego Oddziału Straży Granicznej, które jako pierwsze miały przeprowadzić inspekcję podejrzanego statku. W tym przypadku rolę „statku floty cieni” odegrała jednostka Zodiak II, należąca do Urzędu Morskiego w Gdyni. Ciekawostką jest, że jednostka została zbudowana w Stoczni Remontowej Shipbuilding, gdy jej prezesem był Marcin Ryngwelski, obecnie stojący na czele PGZ Stoczni Wojennej. Oddana do służby w 2021 roku, została uznana za najlepszą jednostkę tego typu na świecie według renomowanego czasopisma branżowego.

W momencie, gdy jednostki straży granicznej zbliżyły się do statku, z jego pokładu zrzucono niezidentyfikowany obiekt – mogący być zarówno dronem podwodnym, jak i ładunkiem wybuchowym. Sytuacja eskalowała, co wymusiło poderwanie do akcji samolotu patrolowego Bryza oraz fregaty rakietowej ORP Kościuszko.

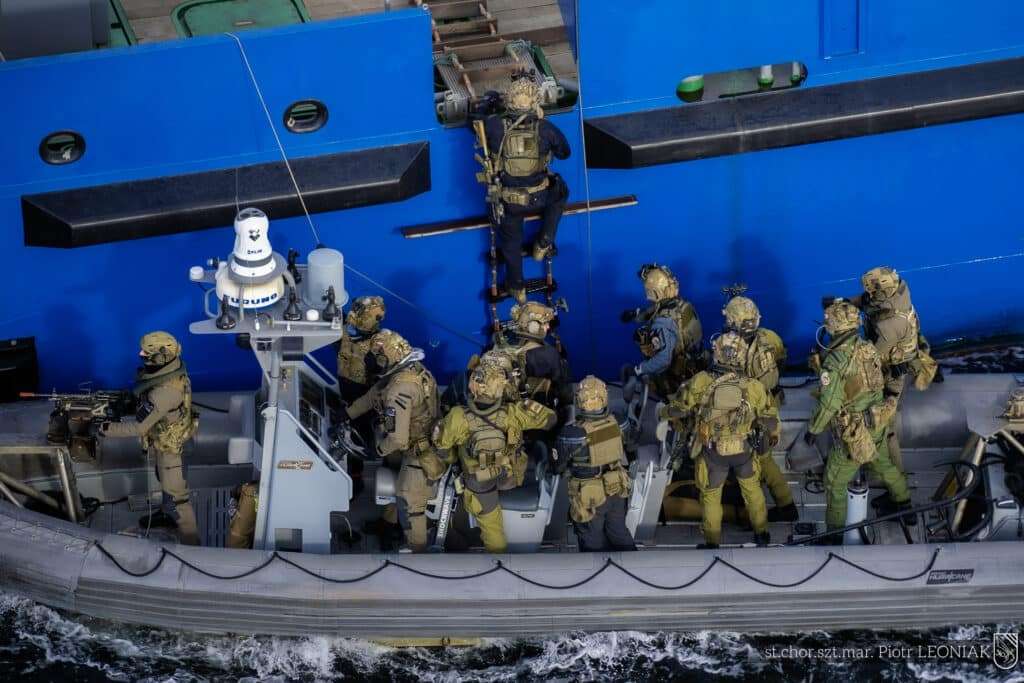

Ćwiczenia te pokazały, jak skomplikowaną operacją jest przejęcie jednostki mogącej stwarzać zagrożenie. Samo dostanie się na pokład dużego statku, który nie współpracuje, może być niezwykle trudne i wiązać się z wysokim ryzykiem dla żołnierzy.

Operacja wymagała perfekcyjnej koordynacji sił marynarki wojennej, lotnictwa, wojsk specjalnych oraz straży granicznej. W ramach symulacji podjęto próbę zmuszenia jednostki do zatrzymania się poprzez demonstrację siły – w tym strzały ostrzegawcze przed dziób statku. Gdy to nie przyniosło efektu, abordaż przeprowadziła Formoza, wykorzystując swoje łodzie półsztywne. Następnie na pokład wszedł Boarding Team fregaty, który dokonał kontroli jednostki.

Podczas operacji wsparcie z powietrza zapewniały śmigłowce Black Hawk z JW GROM, jednak ich rolą było jedynie zabezpieczenie sytuacji z powietrza – nie przeprowadzano desantu. Na pokładzie śmigłowców znajdowali się snajperzy Formozy.

Zagrożenia, na które odpowiadają ćwiczenia „Strażnik Bałtyku-25”, to nie fikcja, lecz realne wyzwania, z jakimi mierzą się państwa regionu. W ostatnich latach na Bałtyku dochodziło do incydentów, takich jak uszkodzenie gazociągu Nord Stream czy przecięcia podmorskich kabli energetycznych i telekomunikacyjnych, co pokazuje, jak wrażliwa jest infrastruktura krytyczna na tym akwenie.

Marynarka Wojenna RP, mimo ograniczonych zasobów i oczekiwania na nowe jednostki w ramach programów Miecznik i Orka, stale doskonali swoje zdolności operacyjne. W najbliższych latach flota ma zostać wzmocniona trzema fregatami Miecznik, co najmniej dwoma okrętami podwodnymi w ramach programu Orka, trzema niszczycielami min Kormoran II oraz okrętem ratowniczym w ramach programu Ratownik. Kluczowym wyzwaniem pozostaje skuteczna ochrona infrastruktury krytycznej – rurociągów, terminalu LNG i portów naftowych – w sytuacji, gdy przeciwnik stosuje nieregularne metody działania.

Ćwiczenia „Strażnik Bałtyku-25” dowodzą, że polskie siły morskie są gotowe na wyzwania przyszłości, choć jednocześnie podkreślają potrzebę dalszego wzmacniania potencjału MW RP. W obliczu dynamicznie zmieniającej się sytuacji bezpieczeństwa w regionie Bałtyku, tego typu manewry mają kluczowe znaczenie dla utrzymania stabilności i odstraszania potencjalnych przeciwników.

Autor: Mariusz Dasiewicz

PGZ Stocznia Wojenna podpisała umowę z Wojskowym Centralnym Biurem Konstrukcyjno-Technologicznym S.A. (WCBKT S.A.) na zaprojektowanie i dostawę przetwornic kontenerowych dla fregat budowanych w ramach programu Miecznik.

W artykule

To kolejny, konkretny krok w budowie polskiego łańcucha dostaw dla nowych okrętów Marynarki Wojennej RP oraz realne wzmocnienie krajowego przemysłu obronnego i stoczniowego.

WCBKT zaprojektuje, wykona i zamontuje dwie przetwornice o mocy minimalnej 950 kW każda, zabudowane w 40-stopowych kontenerach w wykonaniu morskim. Zakres prac obejmie także infrastrukturę zasilającą średniego napięcia oraz system okablowania umożliwiający sprawne przyłączanie i odłączanie jednostki od lądowego źródła energii.

Rozwiązanie pozwoli na zasilanie fregat Miecznik z lądu podczas postoju w porcie. Oznacza to wyższą gotowość operacyjną, mniejsze obciążenie pokładowych systemów energetycznych oraz ograniczenie zużycia zasobów okrętu w czasie postoju. To element, który bezpośrednio przekłada się na efektywność eksploatacji jednostek i obniżenie kosztów ich utrzymania w cyklu życia.

WCBKT to warszawska firma z ponad 50-letnim doświadczeniem w projektowaniu i produkcji sprzętu dla wojska. Przedsiębiorstwo specjalizuje się w naziemnej obsłudze statków powietrznych i pozostaje jedynym w Polsce podmiotem zdolnym do kompleksowego wyposażenia lotnisk wojskowych w sprzęt obsługowy. Wejście w segment morskich systemów zasilania pokazuje rozszerzanie kompetencji o nowe domeny obronne.

WCBKT od lat współpracuje z amerykańskimi partnerami przy projektach lotniczych i lądowych, teraz wspólnie otwieramy nowy rozdział w morskich programach obronnych. Jako spółki Grupy PGZ pokazujemy, że potrafimy sprostać wymaganiom Marynarki Wojennej RP również w najbardziej zaawansowanych technologicznie projektach.

Marcin Ryngwelski, prezes PGZ Stocznia Wojenna

Tam, gdzie to możliwe, stawiamy na polskich partnerów. Każdy taki kontrakt oznacza utrzymanie i rozwój miejsc pracy, transfer kompetencji oraz wzrost udziału krajowych firm w realizacji strategicznych programów modernizacyjnych. Budowa fregat to nie tylko wzmocnienie Marynarki Wojennej RP, lecz także długofalowa inwestycja w suwerenność przemysłową, bezpieczeństwo dostaw i rozwój polskiego przemysłu obronnego.